Cyrus the Great Became Top Leader Of His Era By Championing Just Rule

King Cyrus a Just Ruler

Thursday, July 16, 1998

Investor's Business Daily

Leaders & Success Column

By Matthew Benjamin

When the conqueror Cyrus the Great rode into Babylon, the city's vanquished

erupted in cheers.

Yes, they'd have to bend to his rule. But Cyrus (580-530? B.C.)

made sure that wouldn't be difficult. In contrast to other rulers of his

day, he was just. In fact, his style of government was a critical factor

in his becoming the greatest ruler of his time.

Cyrus' Persian Empire, which extended from India to the Mediterranean

Sea, was the most powerful state in the world until its conquest two centuries

later by Alexander the Great.

Cyrus was born to nobility in a small highland tribe, the Achaemenians,

in central Persia. The tribe paid tribute to several regional kingdoms,

including Media to the west and Babylonia to the south.

Cyrus' father was a minor king who was venerated in his own lands

but became utterly humble when he visited his more powerful neighbors to

take tributes of wild horses.

Once when young Cyrus went on such a trip to Media, he was bewildered

by his father's reduction in stature. More disturbing to him, however,

was the great cruelty of the Median king, Astyages. According to one account,

Cyrus saw

Astyages slay his own general's son as punishment for the general's

minor misdeed.

That same general later betrayed Astyages, causing the king to

lose his authority and possessions.

Such instances taught Cyrus that cruelty and humiliation were

not effective. He decided he would govern through conciliation instead.

Cyrus' first military conquest was of Media in 550 B.C. One of

his first acts was to do away with the draconian tradition that would have

had him raze the city and murder its citizens enmasse.

Cyrus appointed a Mede as chief adviser and then ruled the kingdom

in a kind of dual monarchy, with both Medes and Persians holding high offices.

The satrapy, as this system of government became known, put a native Mede

in power as a semiautonomous ruler, or satrap.

Cyrus instituted certain checks, though. Foe example, several

of the satrap's underlings reported directly to Cyrus.

"Nevertheless, the close relationship between Persians and Medes

was never forgotten. Medes were honored equally with Persians; they were

employed in high office and were chosen to lead Persian armies," wrote

A.T. Olmstead in his "History of the Persian Empire."

From Media, Cyrus went on to conquer the western land of Lydia

and several Greek states on the Aegean Sea. He then turned east, taking

the ancient kingdom of Drangiana, Arachosia, Margiana and Bactria. He converted

most into satrapies

and put natives in command.

He also showed great respect for conquered peoples' religious

and cultural beliefs. At that time, every tribe or kingdom had its own

gods and rites.

While it was customary for conquerors to deface the idols and

religious statues of those they defeated, Cyrus forbade that practice.

When it did occur, he quickly remedied it.

"Large numbers of foreign captive divinities gave further opportunity

for royal benevolence," Olmstead wrote. That earned him the respect and

homage of the races over whom he ruled.

Cyrus' biggest conquest was Babylonia, a wildly rich and powerful

kingdom in the fertile crescent between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers.

It was, however, in decline. Babylonian king Nabu-naid was unpopular with

many segments of his population. He had alienated the high priests and

captured and enslaved ten of thousands of Jews.

Cyrus took Babylon, the greatest city of the ancient world, in

539 B.C. He did so to the cheers of its citizens, who welcomed him as ruler

because of word of his just treatment.

He lived up to that reputation, freeing more than 40,000 enslaved

Jews and allowing them to return to Palestine. He is mentioned 22 times

in the Bible for these and similar deeds.

Cyrus always took pains to convey that he was not a foreign

king and conqueror, but a liberator and, therefore, a legitimate holder

of the crown.

For example, after conquering Babylon, he immediately addressed

its citizens in their own language and added "King of Babylon" to the top

of his long list of titles. It was an unheard of gesture of respect.

"In the eyes of his Babylonian subjects, Cyrus was never an alien

king," Olmstead wrote. "The proclamation of Cyrus to the Babylonians, issued

in their own language, was a model of persuasive propaganda."

He also left in place most of the existing government and allowed

most midlevel officials to retain their positions.

Cyrus was a great learner. He observed the customs and traditions

of the cultures he conquered and made sure the best elements were put to

use for all of Persia's benefit.

Cyrus invented, or appropriated and improved upon, the idea of

the postal system, according to the Greek historian Xenophon. Figuring

out how far a horse could travel in one day, Cyrus built a series of posting

stations,

each one day's ride apart, across his empire. The system ensured the

efficient flow of information between him and his satraps.

|

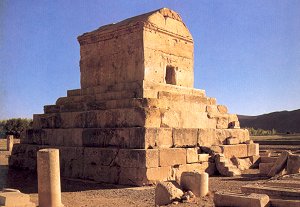

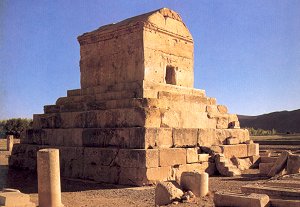

"I am Cyrus, who founded the

empire of the Persians.

Grudge me not therefore, this little earth that covers my

body."

"

O, man, whoever thou art and whensesoever thou comest, for I know that thou wilt come, I am Cryus, and I won f

or the Persians their empire. Do not, therefore, begrudge me this little earth which covers my body.

"

Tomb of The Cyrus The Great (Kourosh) in Pasargad

|

|---|

|